A stunning exhibition for fans of space travel and space art

I took the advantage of a day of annual leave on Monday to visit the Cosmonaut exhibition at the Science Museum. We had considered going at the weekend but decided not to as it was the end of the half term holidays and we thought it would be uncomfortably full. It was a really fascinating show, and I can recommend it wholeheartedly.

As everyone knows, the Russians (or Soviets as they were then) were the first into space. They sent up the first satellites, the first dogs (poor Laika, who never returned, and then Strelka and Belka who did), and the first humans. This exhibition has a fascinating range of exhibits. There are documents like the prescient drawings made by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the first rocket scientist, who imagined with remarkable accuracy in the 1930s what life in space would be like.

A page from Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s Album of Cosmic Journeys, 1932–33. (he Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences / State Museum and Exhibition Center ROSIZO)

There are spacesuits, engineering models, and even some of the original spacecraft which made it back to earth, and which have never before been shown in public.

This was real pioneering stuff and it was fascinating to see it close up. The displays were well arranged so as to allow this. Some of the spacecraft were smaller than I had expected. The first satellite ever launched into space, Sputnik 1, was a small sphere 585 mm in diameter.

Sputnik 1

Image from the Science Museum

The Vostok spacecraft which carried the first cosmonauts seemed tiny and incredibly cramped to me. There’s more space in my Nissan Micra, but Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, spent 3 days in one of them.

Valentina Tereshkova and her actual spacecraft, Vostok 6, at the Science Museum

According to some accounts, she was dizzy and vomited in her space suit, found that the toilet system did not work too well, and may have had her period at the time (Ref). She still managed to spot something amiss with the alignment of her craft, and it turned out that there had been an error in the set-up which would have resulted in her being shot into outer space. Fortunately ground control were alerted and were able to send up a computer programme to correct the error. At the end of the trip, as was the norm for the Vostoks, she had to ejected and parachuted back to earth from an altitude of about 7 kilometres.

The next generation Voskhod capsules seemed no bigger to me, but they managed to cram up to three cosmonauts into them, arranged in a staggered fashion, and looking rather scrunched up.

If you imagine spacecraft to be all smooth, white and glossy, an impression created perhaps by the ceramic-tiled NASA space shuttles, science fiction movies, and Richard Branson’s latest project, the Soviet spacecraft might come as a surprise, with their protrusions, plates and exposed bolts. The space capsules which had returned to earth bore the scars of re-entry. It was not at quite how I expected it to be. I imagine that steampunk enthusiasts would love it.

Image from the Science Museum

Amongst all the historical, scientific and engineering displays, there is a stunning collection of Soviet space art, mostly posters, but also paintings sculpture, well worth seeing in their own right, but given added meaning when displayed in their proper context.

Konstantin Ivanov, The Road Is Open for Humans by Konstantin Ivanov, 1960.

(Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics)

Boris Staris, "The fairy tale became truth", 1961. (Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics)

Iraklii Toidze, "In the name of peace", 1959. Published by IZOGIZ. (Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics.)

There's even a Sputnik samovar for making tea, Russian-style.

Image from the Science Museum

If this last item takes your fancy, there is at the time of writing one for sale on eBay.

Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age

Science Museum, London

ends 13 March 2016

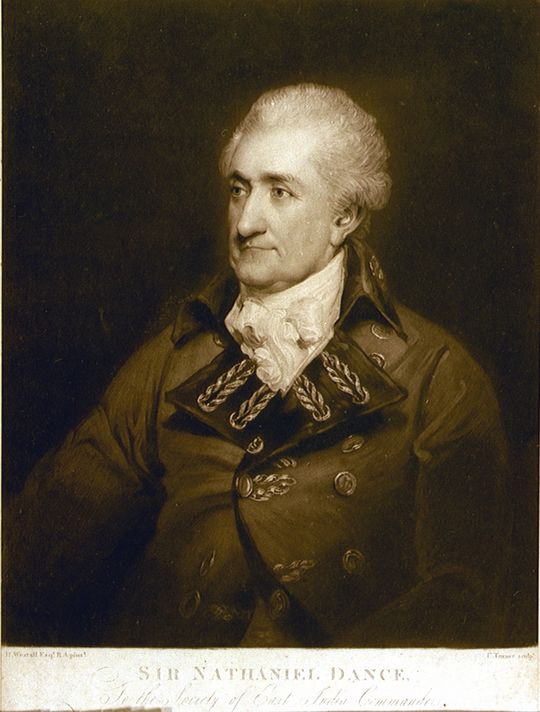

.jpg/300px-The_Fleet_of_the_East_India_Co.,_Homeward_Bound_from_China,_Under_the_Command_of_Sir_Nathaniel_Dance_(tone).jpg)