Napoleonic-era Valentine's Day action at sea, off the coast of Malaysia

Pulau Aur is a beautiful island on the South China sea, about 70 km off the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, with beautiful white beaches, clear water, and an abundance of marine life, popular with tourists, divers and fishermen.

I was there in the late 1980s on a memorable sailing trip on board a large catamaran. It was less developed in those days. I recall an overnight sail with gentle winds during which when we slept on deck when off watch, buying coconuts from a local who came up to sell them from his boat, attempting to make our own sushi from fish we caught, and generally having a good time, as well as some rather heavy weather on the way back to Singapore.

It was only recently that I discovered by chance that the area had been the scene of a Napoleonic naval engagement, known as the battle of Pulo Aura, which took place on 15 February 1804, in the year before Trafalgar.

At that time, trade with India and the Far East was of vital importance to the British economy. India was run by the East India Company. The Company had a fleet of armed merchant ships known as East Indiamen, which carried its goods and passengers. In the time of Nelson and Napoleon, the fighting power of ships was described in terms of the number of guns they carried. The most common large warship (or ship of the line) carried 74 guns. East Indiamen carried up to 36, but the guns were inferior to those of naval vessels, and their crews smaller and less well trained, so while they might be able to defend themselves against pirates or smaller armed vessels, they were not meant for serious naval engagements. However they were painted to look like naval vessels, with extra gunports and dummy cannon, so that they could be mistaken from a distance for more powerful warships. The deception could be effective. In 1797, in the Bali Strait Incident, a French naval squadron was fooled into thinking that a convoy of East Indiamen was a British naval force, and they withdrew without a fight.

The East Indiaman Warley, which took part in the events described.

Robert Salmon, 1801, National Maritime Museum

Every year, a convoy known as the China Fleet, consisting of East Indiamen, as well as smaller merchant vessels, would sail from China and other Far Eastern ports, laden with cargo bound for England. In 1803, Napoleon dispatched a squadron under the command of Admiral Charles-Alexandre Durand Léon Linois to the Indian Ocean to raid British commerce. Notified of the departure of the China Fleet by Dutch informants, Linois set out in search of it.

Charles-Alexandre Durand Léon Linois, by Antoine Maurin

In January1804, the convoy sailed from Canton under the command of Nathanial Dance with an immensely valuable cargo the included tea, silk, and porcelain. In addition, there were 80 Chinese plants ordered by the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks for the Royal gardens, and transported in a special plant room. The only naval vessel accompanying the convoy was a small brig, a 2-masted vessel more suited to carrying messages than fighting in fleet actions.

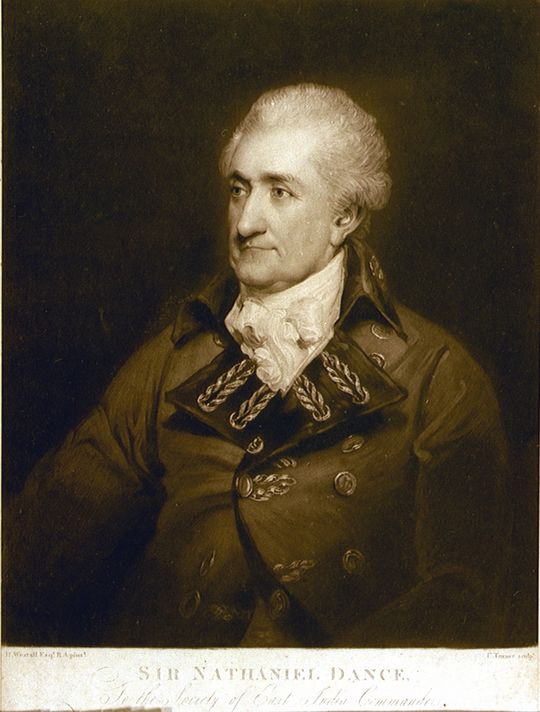

Nathaniel Dance

On the morning of 14 February, within sight of Pulau Aur, sails were sighted by the convoy. Dance sent a few of his ships to take a closer look, and found that this was a French naval squadron consisting of a 74-gun ship of the line, and four smaller vessels of 40, 36, 20 and 16 guns. This was a serious naval force, powerful enough to capture the valuable convoy.

Dance cleared his ships for action, and by 1300 the East Indiamen were deployed in line of battle, the fighting formation used by navies of the day. Linois closed in behind the slower merchant ships, but instead of attacking them immediately, he merely observed. Dance took advantage of the delay to move the smaller unarmed ships to the opposite side of his line, so that his armed vessels were between them and the French. At the same time he gathered volunteers from their crews to supplement the strength of his East Indiamen.

At dawn the following morning, both sides hoisted their colours. Dance had the larger British vessels fly naval ensigns to deceive the French into thinking that they were part of a larger British squadron known to be operating in the Indian Ocean. Uncertain as to the nature of the British ships, the French kept their distance, but as the British fleet redeployed into a sailing formation to continue their journey, the French approached more closely.

By 1300 Dance realised that the French might catch up with the ships at the rear of the convoy, so he ordered his leading ships to turn around and come between the French and the convoy. At 1315 the shooting commenced.

The Indiamen (centre), engage the French (left), and protect the unarmed merchant ships (right)

No serious damage was inflicted on either side, and the only casualties were British: one killed and one wounded, but after 45 minutes, Linois ordered his ships to withdraw from the action and sail away as fast as they could. In order to maintain the pretence that they were warships, and to discourage the French from returning to attack, Dance ordered those ships flying British naval colours to give chase, even though there was no hope of catching the faster French ships. They chased the French for 2 hours before re-joining the convoy. By 2000, the entire convoy was safely at anchor at the entrance to the Straits of Malacca, and they made it back to England without further incident.

The convoy was valued at over £8 million, equivalent to £600 million in today’s money. The loss of the convoy might well have resulted in financial ruin for the East India Company and as well as for Lloyd’s, the underwriters. The captains and their crews were highly praised, and rewarded with prize money and gifts. Nathaniel Dance was knighted, and retired from the sea to Enfield Town, where he died in 1827. The unfortunate Admiral Linois did not have much success after this, and was captured in 1806 when he mistook a powerful British naval squadron in the middle of the Atlantic for a merchant convoy.

Here is Dance's dispatch describing the events:

If you'd like to read a more detailed account of the battle, see Wikipedia.

And finally something else from that convoy which was carried aboard the Warley, the ship illustrated above: an early Chinese music book. http://www.thehistoryblog.com/archives/date/2014/03/09

.jpg/300px-The_Fleet_of_the_East_India_Co.,_Homeward_Bound_from_China,_Under_the_Command_of_Sir_Nathaniel_Dance_(tone).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment